1

Purpose, Design & Implementation

The Purpose and Goals of this Toolkit

provide a means by which individuals or communities affected by a company’s operations can raise questions, concerns, and problems with a company and get them addressed in a prompt and consistent manner. They do not replace judicial or other non-judicial forms of remedy. However, when implemented effectively, grievance mechanisms offer the prospect of an efficient, immediate, and low-cost form of problem solving and remedy for both companies and communities. Strong and trusted grievance mechanisms can help address problems proactively as they arise, before they erode the local community’s trust or become intractable. They can also be an effective way for companies to identify potential problems, and can offer valuable information on how to improve their operations.

Strong and trusted grievance mechanisms can help address problems proactively as they arise, before they erode the local community’s trust or become intractable.

There is growing awareness of the usefulness of grievance mechanisms in helping to address corporate-community conflict. The United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights have been an important catalyst for the development of operational-level grievance mechanisms under the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework,1 while grievance mechanisms, in turn, have played a fundamental role in the practical implementation of the UN Guiding Principles.

The International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) Policy and Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability (IFC Sustainability Framework) recognize that grievance mechanisms are necessary for businesses to responsibly address human rights issues.2 The Performance Standards require client companies to establish a grievance mechanism for affected communities that is scaled to the risks and adverse impacts of the project.3 The Standards further require that clients offer an effective grievance mechanism to facilitate the early identification of grievances and a prompt remedy for people who believe they have been harmed by a client’s actions.

CAO’s casework has shown that, while policies relating to grievance mechanisms might be well-developed, there are still challenges in their application, resulting in a lack of consistency in both the design and implementation of grievance mechanisms at the operational-level. In addition, the perceived and actual costs associated with establishing, implementing, and maintaining a grievance mechanism present another challenge: for businesses with small margins, investing in a grievance mechanism when the need and potential outcomes are unproven may be considered too great an expense when compared to other company priorities.

This toolkit is intended to address these barriers to implementation. It builds on previous CAO guidance on community grievance mechanisms,4 and has two primary purposes. First, it offers a practical guide to designing and implementing effective grievance mechanisms, particularly for

projectswith limited staff, time, and budget. Second, it provides a repository of best practice tools and techniques from CAO’s work, as well as from the work of other practitioners.

Throughout this document, most of the examples used to illustrate the types of

complaintsreceived by a grievance mechanism come from the extractive industries (oil, gas, and mining). Extractive industries have more extensive experience with grievance mechanisms than other sectors, because of the nature of their activities, which can have a high impact on land and water resources, as well as the degree of scrutiny received by the sector. This experience is evidenced by the language used in sustainability reports from extractive industry companies, which commonly focus heavily on community issues, including grievance mechanisms. In contrast, sustainability reports for many agriculture companies have typically placed less focus on these issues. As grievance mechanisms are still an emerging field of practice in sectors other than the extractives, this guide compensates for the lack of quantifiable data by using a number of fictionalized cases that are based on real-life examples from smaller-scale businesses in various sectors.

The specific design and implementation of each grievance mechanism will vary, bringing its own set of challenges and opportunities. This toolkit offers guidance on assessing the local context, determining what might work in a particular situation, and troubleshooting when issues arise.

Find Tools and Resources2

Purpose, Design & Implementation

Why are Grievance Mechanisms a Good Company Investment?

Companies sometimes avoid establishing and implementing a grievance mechanism because of certain “myths” or misconceptions related to their value and potential for success. However, as this section illustrates, the reality is that an effective grievance mechanism can have tremendous benefits for both companies and local communities.

Myth 1. There is no added value for companies, especially small ones, in having a grievance mechanism.

A grievance mechanism that is integrated throughout a company’s operations is a good way to prevent future—and potentially very costly—conflicts. Just as it takes many small drops to make an ocean, a number of grievances left unattended can grow to become more challenging and also more costly.

For example, it is critical to address the concerns of small-scale farmers about large-scale agricultural water use and its potential impacts on water availability before groundwater wells dry up. For issues like this, a grievance mechanism can be an environmental and social risk assessment tool and help to ensure that communities directly impacted by projects can be the first to report issues that might ultimately be costly and problematic in the future. A well-functioning grievance mechanism also provides an opportunity for redress, as well as an opportunity for the company and community to work together to find solutions to problems and develop better relationships. Finally, companies put substantial resources into understanding and eliminating inefficiencies in their management and operational techniques and processes; grievance mechanisms can identify performance gaps by highlighting their impacts on the community (as well as the company) and helping the company avoid or address negative, costly project outcomes.

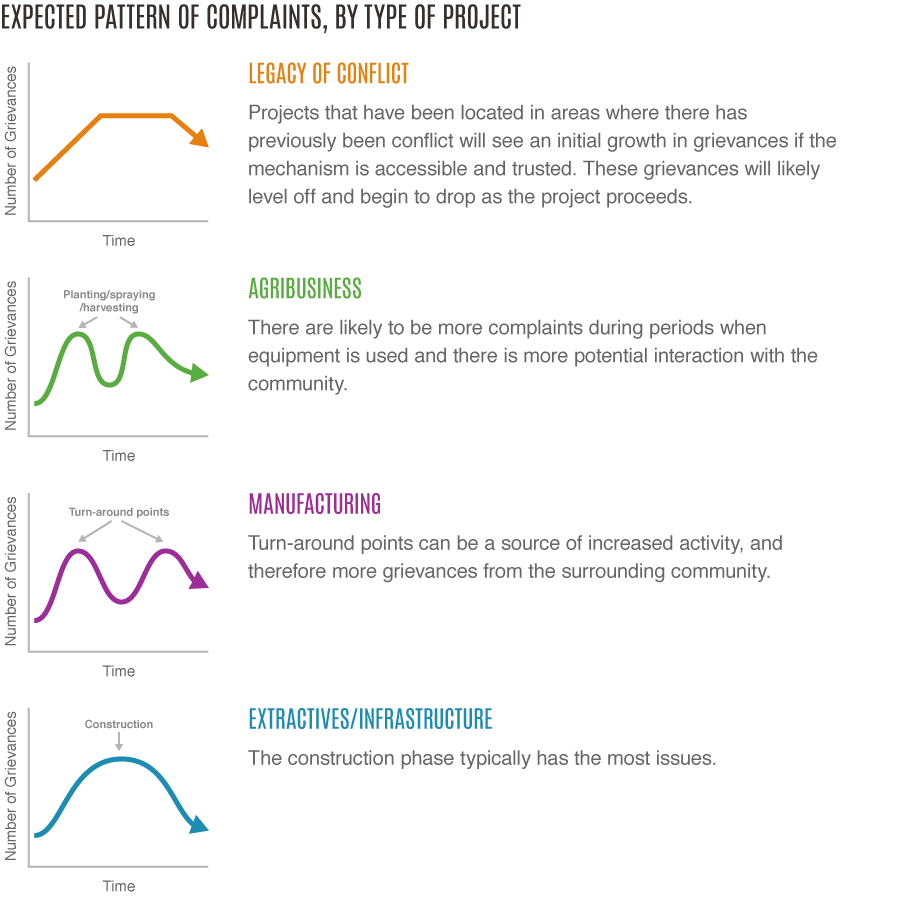

Myth 2. Advertising grievance mechanisms is a bad idea, because you will get too many complaints—and too many complaints will indicate poor performance to management, shareholders, and external stakeholders.

Ideally, companies and communities would exist together in a way that is considered beneficial for everyone. However, for even the best operations, challenging situations will occur throughout the life of the project, from the intensive activities of project initiation or construction to the operational phase, and even during site closure and abandonment. In many cases, complaints are an indicator of community trust in the ability of the company to resolve issues. They also offer an opportunity to address issues while they are still within the company’s control and before they can turn into larger, more challenging conflicts. In fact, more complaints can indicate improved performance and trust of the grievance mechanism.

For example, a major mining company noted in its 2013 sustainability report that it received 2,804 complaints group-wide, and that this number represented a 69-percent increase from 2012. The company further noted that this increase is “what we would expect to see as a result of improvement in reporting.” Forty percent of complaints received related to impacts on communities.5 In this case, the company believed that more complaints indicated better functioning grievance mechanisms and better attention to community concerns. While more complaints are not always a sure proxy that community engagement is going well, they can be a good indication that your grievance mechanism is doing what it is supposed to do in being responsive to project impacts raised by communities.

Myth 3. Grievances are costly to resolve because they are always complicated.

Grievances sometimes involve many people and can be challenging and protracted. This is especially true where there is already conflict - precisely the situations where robust stakeholder engagement is critical. However, because trusted and effective grievance mechanisms are able to catch issues before they are exacerbated and require more resources to resolve, they can actually reduce the potential for unforeseen project costs. This is particularly important for companies with small profit margins.

Grievance mechanisms can also help companies know where and how to allocate resources. For example, if concerns are continually raised about trucks not obeying speed limits on public roads, grievance mechanism data can help a company determine if the speeding issue is related to a particular contractor, which would then need to be sanctioned, or is a systemic issue with company and contractor vehicles, and thus would require a broader education and enforcement program around road safety.

Myth 4. Grievance mechanisms cannot work in communities that are divided.

A grievance mechanism cannot solve every problem a community may face, but establishing a structured, transparent, and reliable process can help heal divisions in communities that are fractured or are emerging from conflict. If the grievance mechanism can serve as a trusted broker in the community, it will provide an important step in rebuilding social capital.

Sometimes a grievance mechanism can be established to address a specific issue that has not been properly addressed in the past. For example, land tenure and resettlement are fundamental issues for many projects, and may require a dedicated and specific grievance mechanism to address what is often a legacy of uncertainty. At one operation in a post-conflict country in central Africa, a major resettlement accounted for half of the complaints received group-wide for all operations of a multinational mining company. The land and resettlement issue required an issue-specific grievance mechanism to be developed. The company also set up an Independent Mediation Committee (IMC) to resolve grievances that could not be resolved using the basic process. The establishment of the grievance mechanism and the IMC was a major step toward resolving conflict and divisions in the community.6

Myth 5. Grievance mechanisms will always be flooded with complaints and will consume substantial company resources forever.

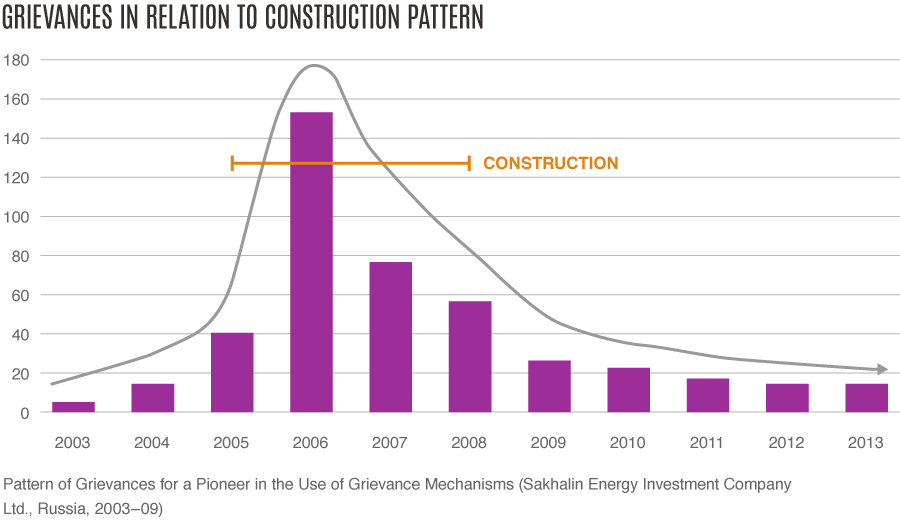

The experience of one of the first energy projects to implement a grievance mechanism, Sakhalin Energy Investment Company Ltd., in Russia, is instructive. The company’s grievance mechanism became functional in 2003, as the project was transitioning from design to construction. At the peak of construction, the project received approximately 150 complaints in one year. As construction activity decreased, the number of complaints received per year decreased to approximately 15 (see Figure 1).7 This example demonstrates a common phenomenon: the number of complaints received correlates with the amount of activity on the ground and the corresponding impact on the community.

Myth 6. An

operational-level grievance mechanismmanaged by a company does not have legitimacy, and the outcomes cannot be trusted.

Some community members and the groups that work with them have a difficult time believing or understanding how a mechanism developed and managed by the company causing the adverse social, economic, or environmental impacts in question can lead to equitable outcomes. This feeling can result from deep-seated mistrust of a particular company, the private sector in general, or past experience with poorly designed and implemented grievance mechanisms. These concerns are legitimate as there are many examples of companies that have not worked in good faith with communities impacted by their projects. However, experience with grievance mechanisms implemented for natural resource projects shows that most issues raised by community members relate to operational impacts from the business (e.g., the day-to-day issues of industrial operations such as noise, dust, and traffic) and the benefits business provides (including jobs, contracts, and social investment). These types of issues can be addressed quickly, efficiently, and cost-effectively through a well-structured grievance mechanism. Such a grievance mechanism can serve as an effective first point of call for community concerns that arise from day-to-day operations. Grievance mechanisms also do not preclude a

complainantfrom pursuing other options, such as another complaints mechanism or a legal or regulatory process, if the grievance mechanism does not provide a satisfactory process or outcome. If affected communities are consulted during the development of the grievance mechanism, the company keeps its promises, and the complainants experience a fair process and redress, then credibility and legitimacy of the mechanism can be achieved (see Section 4 for more on building trust in a grievance mechanism).

Related Tools and Resources

This case is particularly helpful for projects/operations with a large land footprint; operations that may be in competition with local means of income generation or subsistence; and agricultural producers.

3

Purpose, Design & Implementation

Issues to Consider when Establishing a Grievance Mechanism

There are several issues to consider when making the decision about whether and how to establish an

operational-level grievance mechanism.These include the costs associated with the creation of a grievance mechanism, as well as ways to ensure that both the company and the community gain maximum benefits from it.

While the upfront costs may seem high, if the grievance mechanism is “fit-for-purpose,” the benefits will outweigh the costs.

Costs Associated with Grievance Mechanisms

There are various costs associated with establishing, implementing, and maintaining a grievance mechanism. While the upfront costs may seem high, if the grievance mechanism is “fit-for-purpose” (i.e., it is scaled to the risks and potential adverse impacts of the project), the benefits will outweigh the costs. This is particularly true for businesses that would not be able to afford the necessary response if conflict arises or becomes protracted because community grievances have not been effectively addressed. A recent study by the University of Queensland in Australia showed that, in the extractives sector, costs from community disruption and conflict can range from US$10,000 to US$50,000 per day during exploration, and up to US$20 million per week during operations. Although the study focused on the extractive industries, a sector with a long history of tracking costs related to conflict, the general lesson is applicable to any sector.8

Maximizing Resources and Capacity: Local Context Matters

When a company invests in a grievance mechanism, it needs to ensure that both the company and community are getting the most value out of it. It is critical to address local context, so that resources can be applied where they are most likely to be needed. While it is impossible to anticipate all issues, there are some key questions to consider when thinking about the best way to scale the resources and capacity necessary for establishing a grievance mechanism.

Will the grievance mechanism be dealing with specific issues?

In some instances, grievance mechanisms will be targeted toward specific and repeated issues that arise on a particular type of project. For example, for many agricultural projects, damage to surrounding crops can be a frequent problem. In this case, a grievance mechanism could have a particular focus on this issue and thus include specific processes such as agricultural inspections.

In the best of circumstances, a grievance mechanism and associated staff will have sufficient trust with community members that it would serve as the first place to go for any issues, regardless of scope.

Will the grievance mechanism be dealing with multiple issues from multiple perspectives?

In other cases, a grievance mechanism could be the point of entry for many issues, from social investment to employment to managing impacts on infrastructure. For example, projects that require facility construction have short-term and intensive impacts related to traffic, noise, dust, the availability of services, and supply and demand of skilled and unskilled labor. In this case, it would be important that the grievance mechanism have few restrictions on scope and eligibility, so that it can serve as the first point of entry for any community concerns. In many instances, community complaints would be addressed within the grievance mechanism, but in some instances a complaint may be assigned to another department with its own process (such as human resources, in the case of a complaint related to employment). In the best of circumstances, a grievance mechanism and associated staff will have sufficient trust with community members that it would serve as the first place to go for any issues, regardless of scope.

How will the grievance mechanism work with indigenous groups or vulnerable people?

When indigenous groups or vulnerable people are present, specific processes will need to be in place to ensure the mechanism works equally well for them. For example, it may be necessary to have a grievance officer from a local indigenous group or to ensure female representatives are available to discuss and receive complaints in places where women do not customarily express concerns publicly. In addition, it is imperative that communications be in the local or indigenous language, to facilitate accessibility and understanding.

Making sure that the grievance mechanism takes the local context into account will ensure it is fit for appropriate and specific purposes and risks.

Do contractors have a role in the implementation and functioning of a grievance mechanism?

For many projects, contractors conduct the bulk of activities. For example, when a project requires large-scale civil works, the construction is typically completed by contractors. Although contractors may be engaging in activities that result in complaints, the owner or operator is usually the “face” (public point of contact) of the project, and any complaint related to a contractor will also reflect poorly on the operator. In some cases, contractors have implemented their own grievance mechanisms. In other instances, owner/operators have chosen to implement a grievance mechanism that is managed by their own staff, but involves contractors and the public as applicable.

Is the grievance mechanism “fit for purpose” and scaled to the issues and risks anticipated?

In all cases, a good grievance mechanism incorporates local circumstances while following a consistent and structured process. Making sure that the grievance mechanism takes into account the local context will ensure it is fit for your specific purposes and specific risks. It will also mean that resources are put to good use by focusing on the real issues related to the project, rather than creating a mechanism that looks good on paper but does not actually help to identify and address issues raised by the community.

Related Tools and Resources

This case study is particularly helpful for projects: with an existing operation/facility; located in an urban or densely populated area; that have an operation/facility that could be contributing to cumulative impacts; that have an operation/facility that has impacts that may require further investigation.

4

Purpose, Design & Implementation

Building a Good Grievance Mechanism

It is important to consider how a grievance mechanism fits into the company’s overall engagement strategy. As a general goal and measure of effectiveness, the grievance mechanism should be part of a broader approach toward stakeholder engagement that provides a way for community members to consistently engage with the company, enhances relationships, reduces social risk, and enables more responsive and responsible management.

The specific objectives of a grievance mechanism should include:

- 1establishing a timely, consistent, structured, and trusted procedure for receiving and addressing community concerns and complaints;

2ensuring that

complainantsare treated with respect;

- 3ensuring proper documentation and disclosure of complaints and any resulting corrective actions; and

- 4contributing to continuous improvement in the company’s performance by analyzing trends and learning from complaints received.

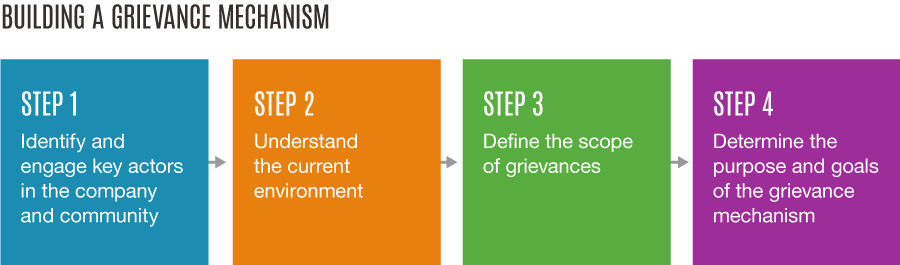

Getting started: Initial steps for building a grievance mechanism

The four main steps for the initial development of a grievance mechanism presented in this section should work across most contexts and situations. These steps include: identifying and engaging key actors in both the company and the community; understanding the current environment; defining the scope of grievances; and determining the purpose and goals of a grievance mechanism.

Step 1: Identify and engage key actors in the company and community

As a first step in the process of establishing a grievance mechanism, company staff tasked with this responsibility should identify supporters of the mechanism within both the company and the community, and cultivate their leadership. When identifying champions within the company, it is important to find people who have decision-making authority. If it is challenging to find someone who fits these characteristics and is also interested in the grievance mechanism, then identifying a key operational person who is well-respected in the company and presenting the business case for grievance mechanisms may help. It is also useful to consistently demonstrate the success of the grievance mechanism as it begins to operate.

Effective stakeholder assessment is necessary to identify leaders within the community who are trusted by the community. At this initial point, it is also important to ensure that there is representation from different community groups (such as women or indigenous people). They will help develop an understanding of what constitutes an effective grievance mechanism and eventually assist with communication about the grievance mechanism, and educate others on the mechanism.

This step is important, because it helps to ensure that different perspectives have been considered in the design process; that the key decision makers are committed to the process; and that they will respond to complaints quickly. Identifying key actors also helps to build trust between the company and the community, and allows the company grievance mechanism staff and the community to be able to engage with each other in a constructive way.

Feedback from the community will be invaluable in later determining the potential scope of grievances.

Step 2: Understand the current environment

Once the key stakeholders are identified and engaged, company staff and their community partners should conduct an assessment of the types of grievances that are likely to arise and any existing local methods, procedures or capacity to handle them. In addition, if the project is already operating, the team should determine the nature of any community grievances that have been presented thus far. Understanding the current environment will involve visiting the community as much and as often as possible, to determine what kinds of concerns community members have about the project and the ways in which they traditionally solve conflict. Company staff can also communicate their own ideas about what a grievance mechanism in the area might look like. Feedback from the community will be invaluable in later determining the potential scope of grievances. This step helps to determine what sort of grievance mechanism will be fit for purpose for the project, by outlining the tools that are already available within the community and the types of complaints the mechanism will likely have to address.

Step 3: Define the scope of grievances

Working with community members and company management, the staff members who are setting up the grievance mechanism should determine the breadth of complaints that might arise. This will involve identifying the points where the community and the company’s everyday activities come into contact, and also determining whether people are likely to bring grievances as individuals or as groups.9

As with understanding the current environment, this step involves visiting the community frequently and also speaking with people involved in carrying out the daily operations within the company, to identify when and under what circumstances they interact with community members. This will provide a foundation for the next step in the process: determining the purpose and goals of the grievance mechanism. If there is an understanding of the scope of grievances, it is easier to decide whether and how the grievance mechanism will be able to handle these issues. This step also helps to assess what level of resources will be needed for the grievance mechanism.

Step 4: Determine the purpose and goals of the grievance mechanism

As a final step in the initial implementation process, company staff should work in collaboration with community members to answer the following questions: “Why is a grievance mechanism being established, and what do we hope to achieve in the short term and the long term?” They should consider whether issues such as complaints regarding criminal activity, labor grievances, commercial disputes, or government policy issues would fall within or outside the scope of the community grievance mechanism.

This step is important for establishing a common understanding between the community and the company about which issues the grievance mechanism will, and will not, address. To this end, meetings within the community, and between the company and community are critical. If consensus on the grievance mechanism cannot be achieved, then one or the other party will not consider it legitimate, and even the best-designed grievance mechanism will not provide the feedback necessary for the company to remedy community concerns and also manage risk.

Building Trust in a Grievance Mechanism

Trust is essential to a grievance mechanism. People need to know that it is a safe place to seek redress, that their confidentiality will be protected, and that they will not be subject to retaliation by either the company or other community members when they voice their concerns and participate in the grievance resolution process. Further, participation in an

operational-level grievance mechanismis always voluntary and community members need to know they can freely choose not to participate, or can cease to participate without retribution. In some particularly difficult circumstances, it may be necessary to identify an ombudsman in the community who can hear and respond to any allegation of retribution, whether this be open criticism of the project, presentation of a complaint, or dissatisfaction.

Communication is also key to building trust. It is especially important to tell people what they can expect once they have decided to submit a complaint and what the complainant can expect from the process, together with any uncertainties. The steps in the process should be clearly outlined to the complainant, with clear, frequent, and timely points where information on the process is communicated

An effective grievance mechanism relies on trust between community members and the company and an assurance that lodging a complaint will not have negative repercussions on the complainant.

A lack of clarity on the process can lead to confusion and ineffectiveness of the grievance mechanism. For example, an oil and gas company in the Middle East set up a grievance mechanism to manage community concerns over project impacts, including noise, traffic, and dust. It also set up a Local Development Council composed of authorities and company contracting and procurement staff to address employment opportunities. However, community members seeking opportunities with the project saw the grievance mechanism as a place to receive special attention from community relations staff, who felt pressure to respond rather than refer the community members to the Local Development Council. This misunderstanding resulted in confusion and lack of effectiveness of both the grievance mechanism and the Local Development Council.

Managing expectations is also necessary for generating and maintaining trust. Key activities for managing expectations include discussing different scenarios for what the complainant can expect and letting people know about the limitations of the process early and often.

An effective grievance mechanism relies on trust between community members and the company and an assurance that lodging a complaint will not have negative repercussions on the complainant.

Related Tools and Resources

Identifying who is responsible for different elements of grievance mechanism implementation and operation

Useful for: company managers, operations staff, grievance mechanism implementers

This case study is particularly helpful for projects/operations: in the exploration or development phase of a project; in an area where the local community depends on land for income (e.g., farming); in a situation that require the extensive use of subcontractors.

Identifying the best qualities and qualifications for dedicated grievance mechanism staff or identifying staff in other company roles who might be the most effective contact person for the grievance mechanism

Useful for: company managers, grievance mechanism practitioners

5

Purpose, Design & Implementation

Making a Grievance Mechanism Work

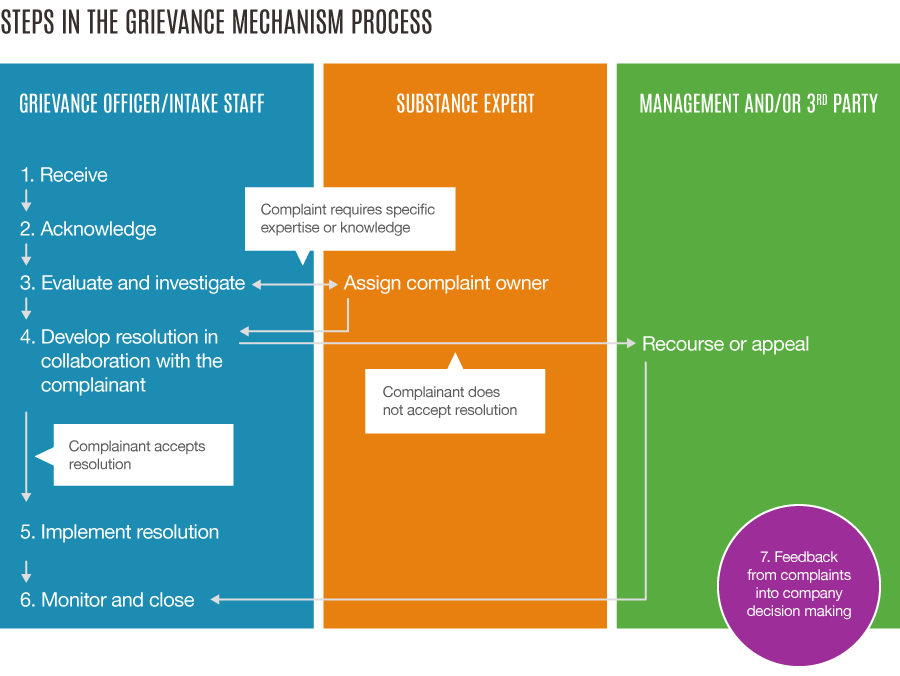

After the initial stages of building the concept of a grievance mechanism, establishing trust, and identifying key company and community focal points, it is time to focus on structure. The scope and goals of the grievance mechanism will be determined by the scope and size of the project. While some grievance mechanisms will have to be large and complex, because they are associated with large and complex projects, others will not.

There are six basic steps involved in a grievance mechanism (see Figure 4). These six steps are the minimum number required for a functional mechanism. In some cases, complaints will be managed completely by the Grievance Officer (left side of the flow diagram in Figure 3) and will not need to be assigned to another

complaint owneror escalated to an appeals committee. Even for complex sites, only a fraction of complaints typically need to be escalated for appeal, negotiation, or mediation. The steps of a basic grievance mechanism workflow include:

- 1Receive: A question or complaint from a community member or members is received by the company Grievance Officer.

- 2Acknowledge: The Grievance Officer acknowledges receipt of the complaint within a specified period of time (usually 3-5 working days).

- 3Evaluate and Investigate: The Grievance Officer conducts a timely evaluation of the complaint to determine if the issue can be resolved without the involvement of other company staff.

- If so, the Grievance Officer is the owner of the complaint.

- If not, the Grievance Officer assigns another company staff member as owner of the complaint (usually someone from the area of operations related to the complaint).

- 4Collaborative Resolution: In consultation with the complainant and any other relevant company staff member, the complaint owner proposes a solution and presents it to the complainant.

- If the solution is not accepted, the Grievance Officer or complainant can present it to an appeals committee or the complainant can seek recourse through another mechanism (e.g., a legal process).

- 5Implement Resolution: If the solution is accepted, it is implemented.

- 6Monitor and Close: Once the complaint is resolved, or if the complainant does not accept resolution and chooses to engage in another process, the complaint is monitored for a reasonable period to make sure the complainant does not express additional concerns and then closed. The process and outcomes of the complaint are evaluated by management as part of ongoing company-community engagement, risk assessment, and strategic analysis.

The Appeals Committee

Grievance mechanisms often incorporate appeals procedures to allow complainants to seek alternate recourse if they are not satisfied with the resolution offered by the company. The appeals process offers a chance to resolve complex complaints.

The first line of appeal is often internal to the company. In such cases, to avoid a conflict of interest, the party hearing and investigating an appeal should not be the party that initially investigated the complaint and worked with the complainant to define a resolution and approach. In many cases, the complainant’s appeal will be handled by senior managers who are designated within the company to address unresolved complaints and who were not previously involved with the issue.

If the internal appeals process does not satisfy the complainant, a grievance mechanism may also incorporate an external appeals approach as the next resolution option. Including this option may encourage complainants to continue to pursue resolution through the grievance mechanism, even for complex issues. This may help to avoid the concern that the company creating the problem serves as the de facto judge and jury with limited additional routes to remedy. External appeals approaches vary widely and can include third-party involvement for mediation or non-binding arbitration. Depending on the culture and local customs, an external appeal could involve a tribal chief, ombudsman, trusted official, religious figure, or others.

The company and complainant should agree on the selection criteria and process for involving a third party. Early engagment will help generate trust on both sides that the appeals process will be fair and impartial.

If third-party recourse is not possible or does not work, the complainant still has access to available judicial procedures without fear of retribution or retaliation.

As management, you play a critical role in helping to demonstrate that the grievance mechanism function is a valued part of the performance and success of the company.

Incentives

In this document, we stress the need for all company staff to be aware of the importance of grievance mechanisms and to be involved in the resolution of grievances. This is not simply the role of the person in charge of intake and coordinating the grievance mechanism process, even if there is a person dedicated to that task. In the end, most complaints intersect with the technical elements of a company’s operations, meaning that company staff will be required to provide potential resolution input to complaints received. Management plays an important role in ensuring that this engagement is meaningful by providing the right incentives to all staff. For example, when operations staff have gone beyond the agreed upon timeline for the resolution of a complaint, this could be raised as part of regular department meetings. For staff that consistently go over the agreed timelines, this could be a point of reference in a performance review that has implications for rewards. On the other hand, staff that are consistently involved in timely resolution of complaints and receive good feedback from complainants may receive a bonus or company award for their efforts to engage in positive stakeholder relations with community members. Every company has methods of rewarding good behavior and punishing bad behavior and this helps to set the culture of what is important in an organization. While we may outline good practice in this document, if it is not accompanied by tangable incentives for staff, it may never succeed. As management, you play a critical role in helping to demonstrate that the grievance mechanism function is a valued part of the performance and success of the company.

Related Tools and Resources

Rapidly assessing the potential challenge areas of existing grievance mechanisms

Useful for: grievance mechanism experts

This case study is particularly helpful for projects/operations with: inherited issues from a previous operator; issues of compensation; a large land footprint; or in the exploration or development phase of a project.

Assessing which barriers may be causing a grievance mechanism to be ineffective and identifying possible solutions

Useful for: managers, operations staff, grievance mechanism implementers

6

Purpose, Design & Implementation

Closing the Loop: Using Grievance Mechanism Feedback to Improve Business Practices

Once the work of designing and establishing a grievance mechanism is finished, it is important not to stop there. As management, one way to get the most value from the investment is to make sure that information about complaints is used to make course corrections for current or potential problems with operations. For example, if, over the span of a few months, several complaints have been lodged about company expansion onto land that the company feels it has title to but is also claimed by community members, conflict is likely. Grievance mechanism data can be used to determine if the concern is related to a particular location or a group of people that would need attention from the company, or if it relates to a broader issue about land titles that involves multiple locations and groups of people and could require a broader effort, such as formation of a multistakeholder land compensation committee.

Some parameters that can help inform company policy and response, as well as provide evidence for the effectiveness of the grievance mechanism, include:

- 1Average time to respond to a complainant (Is this consistent with the response target?);

- 2Average time to resolve a complaint (Is this consistent with the complexity of the complaint?);

- 3Complainant’s overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the resolution of the complaint;

- 4Comparison of the cost of stoppages associated with the project before and after the grievance mechanism has been implemented (This is a good way of demonstrating the effectiveness of the grievance mechanism.);

- 5Complaints per location (such as field, town, village, municipality);

- 6Complaints per unit (such as construction, contractors, farm laborers, pipeline); and

- 7Complaints per issue (such as land, water, noise, compensation, pollution).

Additional questions to ask include:

- 1Are there any trends by location, unit, or issues?

- 2If there are trends, is this problem very targeted (such as a truck driver who is driving too fast), or would it require a more systemic solution (such as a foul smell coming from the farming operations when fertilizer is applied)?

- 3If complaints are clustered around particular issues, should a department outside community relations become more involved in grievance management? For example, if there are numerous complaints about employing more local workers and awarding more contracts to local service companies, it would be difficult to make progress unless contracting and procurement staff are involved.

- 4How often should management meet to discuss complaints? Should a report be compiled and considered during the next round of some change-management process? Should external consultants be engaged to help build the findings into a reorganization of the managerial system?

- 5Are there site-level operational changes that should be instituted by management to address high-volume complaints? For example, if complaints cluster around nighttime noise from operations, would it be possible and effective to implement noise abatement methods or shift the work pattern such that noisy activities only occur during daylight hours?

- 6For companies with multiple operations, are there lessons to be learned from the complaints received at a particular site that can be applied to other sites? For example, if citizens express concern around the fairness of hiring at a particular operation, could this information be used to develop more participatory and transparent hiring practices at operations that are just starting up?

Answers to these questions can be used to develop changes in operations or the management structure that could decrease complaint frequency.

Once a method is established for management to receive and respond to grievance mechanism data, it is important to keep the community and other relevant stakeholders informed of that process. This transparency helps to maintain trust. It also helps to ensure that when systemic issues do arise, management will be responsive, gather any supporting data and research, and incorporate community member input into effective and fair resolution of the issues.

Some Closing Thoughts

Grievance mechanisms have become a key and, in many cases, required component of responsible business practices. They offer value to companies and communities in any industry. While it can be challenging to establish a grievance mechanism, the process and the grievance mechanism itself do not have to be complicated. Fitting a grievance mechanism to the local context in a way that is manageable and trusted by all parties is one of the most important ways to achieve success.

The tools in this toolkit are intended to act as a guide to establishing and implementing grievance mechanisms by giving examples of how others have done it, and by demonstrating some practical ways of implementing broader principles. They are meant to be used as a starting point, with the understanding that they will need to be modified for each context. Above all, it is important to get started!

Related Tools and Resources

Finding resources and definitions for different elements of a grievance mechanism and responses to frequently asked questions

Useful for: company managers, operations staff, implementers of grievance mechanisms

This case is particularly helpful for projects/operations: in an area where community perspectives on the operations are divided; in a community with a large indigenous population; in a remote location.